July 2019 Client Letter

You may have concerns about today’s environment and how a variety of risks could impact the long-term health of your finances. One of the biggest concerns we all face is interest rates that have been so low for so long.

Jim Grant writes in his Grant’s Interest Rate Observer newsletter, “almost $13 trillion in debt world-wide is priced to yield less than nothing. Mostly, it’s just a little less than nothing, but, still, a little less than nothing isn’t much to retire on.” He calls this a 4,000-year low in bond yields.

What kind of investor would buy negative yielding bonds? Writing in Barron’s, Grant points the finger at passive bond investors:

Peter Chiappinelli, a portfolio strategist at GMO, Boston, says he has given it considerable thought. In a sense, the buyer is the aforementioned Global Agg index, though the index hardly buys itself. The mystery buyer, Chiappinelli says he has come to see, “is anybody who owns a passive mutual fund tied to the Global Agg. Or anyone who might now own a passive ETF tied to a global bond index. Or anyone who owns a popular target-date fund that has passive exposure to global bond indexes. In other words, millions of Americans.”

Good Policies—Not Easy Money—Are

What Help the Economy and Your Portfolio

Can you believe how much attention is paid today to the Federal Reserve and central banks around the world? Does anyone really think the Fed is the reason the economy does well, or falls apart? Certainly, the Fed can cause problems by raising rates too high and choking off growth. But for the most part, the Fed is not the reason for a healthy economy. Some primary drivers for a healthy economy are creating and maintaining an environment where individuals can easily form businesses and be free to innovate.

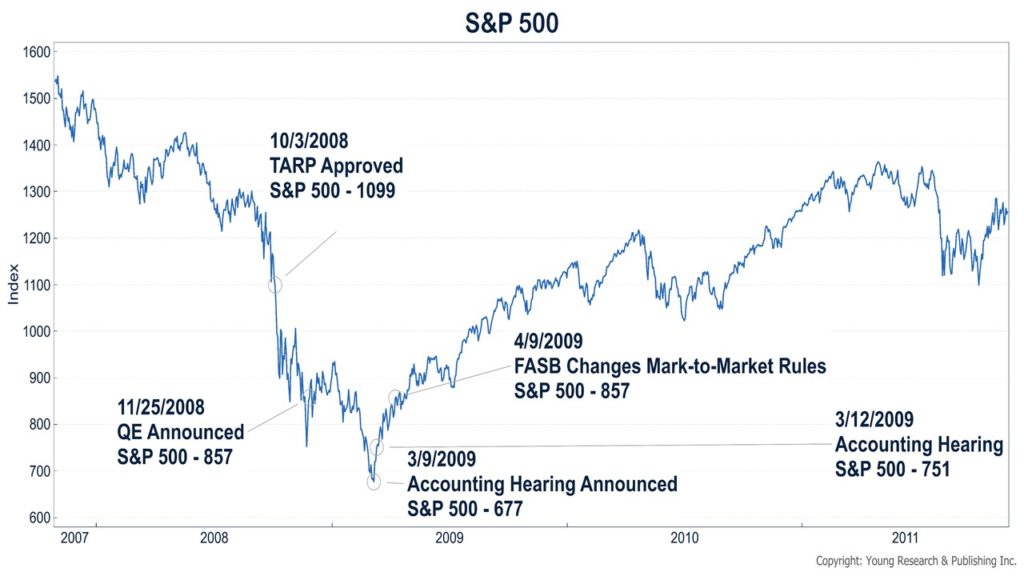

The Fed is one of the last places to look for help bolstering long-term growth potential or raising America’s standard of living. By example, look back at the financial crisis. Many believe the $700-billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) coupled with quantitative easing (QE) by the Fed were responsible for our rescue. TARP was signed into law in early October 2008 while QE was announced in November 2008. From the period TARP was signed, through March 9, 2009, the S&P 500 fell 38%, the S&P Financials Index fell over 60%, we saw a decline in GDP, and the unemployment rate increased.

In our view, the turning point for the crisis came in early March 2009, when Barney Frank, chair of the House Financial Services Committee announced there would be a hearing on mark-to-market accounting on March 12.

As Brian Westbury explained in a 2013 blog post, changes in the rules for mark-to-market accounting in 2007 created a negative feedback loop that turned what might have been a big problem into a disaster (emphasis—underlined below—is ours).

It wasn’t until early March, when FASB finally agreed to change M2M accounting that things turned around. The reason for this is simple. As long as assets were priced to illiquid market prices, the banking system would continue to contract because lower marks would lead to less capital, which would lead to more selling and less liquidity, which would lead to lower prices. It was a vicious, and unstoppable, downward spiral. Private investment money dried up. Both TARP and QE were designed to fill the hole left by this ill-advised accounting rule.

To put this in perspective, AIG, the poster child for those who believe in the conventional wisdom, had a $550-billion portfolio of credit default swaps. When marked to the market in the winter of 2008–09, this portfolio had a massive hole (loss) of more than $100 billion. However, once the economy settled down, mark-to-market rules were relaxed and liquidity returned, this hole disappeared, prices increased, and the portfolio actually turned a profit.

It was the accounting rule itself that dried up liquidity in the winter of 2008/09. Even if cash was flowing, just the idea that it could stop pushed prices down. As a result, M2M accounting rules kept investors away because they threatened a vicious downward spiral in the financial system.

Milton Friedman explained in his book “The Great Contraction” how mark-to-market rules, not bad loans, caused bank failures in the early 1930s. In 1937, FDR eliminated M2M accounting. Between then and 2007, the economy has avoided panics and depressions. We do not believe this is a coincidence. Some argue that with no strict rules, banks can hide losses. But this is not true. A bad loan is a bad loan, and more than 2000 banks and S&L’s (sic) failed between 1983 and 1994 without having strict M2M rules.

At the hearing, Congress told the leadership of the Financial Accounting Standard Boards, in no uncertain terms, that they (FASB) needed to make significant changes to the mark-to-market accounting rules or Congress would step in.

The chart below shows the timeline of events related to TARP, QE, and the change in mark-to-market accounting rules. Anybody arguing it was TARP or QE that turned the tide during the financial crisis may need to take another look at the evidence.

A Disappointing Development for Income Investors

Unfortunately, our wishes for sound money and prudent monetary policy are the way we want the world to be, not the way the world operates.

Much to our dismay and most likely yours, the Fed looks set to cut rates again, and with those cuts come a more challenging environment for bond investors. This is a disappointing development. As of the fourth quarter of 2018, yields appeared to be rising and we hoped we were beginning to claw our way back to a more-normal yield environment.

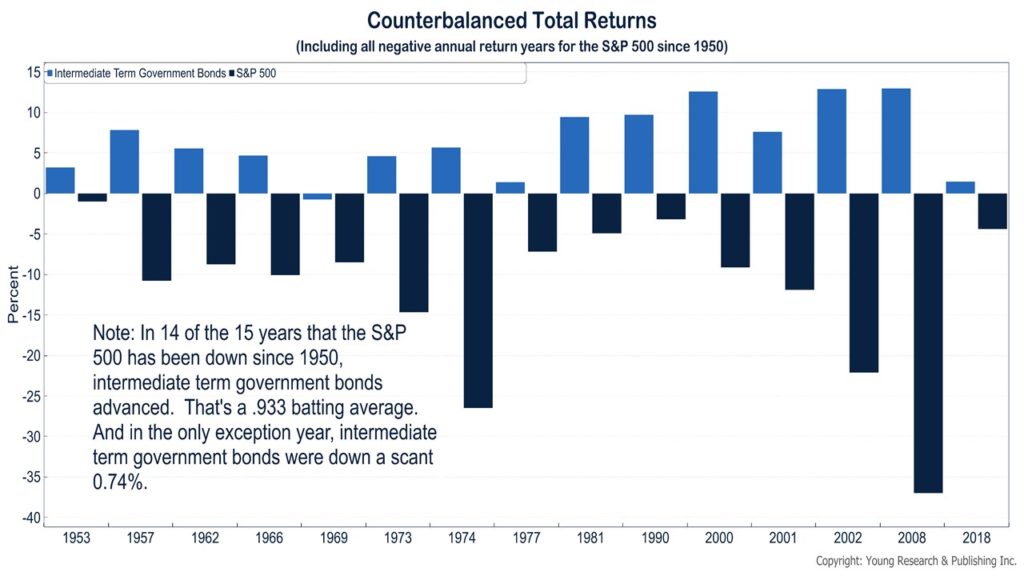

You, like many investors, most likely look to your bond allocation as a way to generate income and reduce overall portfolio risk. This is certainly our strategy. Bonds provide a vital counterbalance to equity markets during times of stress. In 14 of the 15 years that the S&P 500 has declined, intermediate-term government bonds have advanced. A hypothetical portfolio invested 50% in intermediate-term Treasuries and 50% in the S&P 500 in 2008 would have declined 12% compared to a 37% loss for the S&P 500. Those approaching retirement who are investing in an all-stock portfolio are rolling the dice. A market down 37% one year before retiring requires a major downgrade in one’s retirement standard of living.

Bond Investing in a Low Interest Rate Environment

Bonds are “must own” even in a low-rate environment, but navigating the bond market when yields are in the tank is a tall order. The temptation is to reach for yield in low-grade bonds, but 10 years into an economic expansion is no time to pile on credit risk. What’s more, diving into the highest-yielding bonds with no regard for proper portfolio construction can backfire.

Do You Know Which Bonds Go Best With Stocks?

In the hypothetical example I provided above, if instead of purchasing Treasuries the investor purchased high-yield bonds, the 50-50 portfolio would have fallen 32% in 2008, with the bond portion cratering 26%.

High-yield bonds act more like stocks in a down market, which makes them a poor complement to an equity portfolio most of the time. There are, however, occasions when high-yield bonds make sense. And in this low interest rate environment, knowing when to take the risk in high-yield bonds and when not to take that risk can make a world of difference.

Over a Million Bonds to Choose From

Just like with stocks, not all bonds are created equal. There are over one million bonds in the Bloomberg database to choose from for the U.S. alone—all with varying terms, features, and risks.

Sifting through the database, let alone crafting a portfolio that generates a stream of interest income and the proper amount of counterbalancing power for every stage of the economic and credit cycle, is a whole other matter.

The Bonds We Are Buying for You

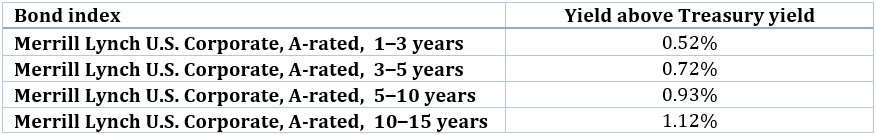

Our focus in fixed income at this stage of the cycle is a mix of Treasury securities and higher-grade corporates with a short-to-intermediate-term all-in maturity structure. We are extending maturities somewhat in corporates, and shortening somewhat in Treasuries. The longer-term corporates offer more compensation relative to government bonds than short-term corporates. The table below shows the spread or additional yield relative to Treasury bonds for four A-rated Merrill Lynch U.S. corporate bond indices. Note the longer the maturity the greater the yield above Treasuries.

Bonds That Bounce

Longer maturity bonds, if of a high-enough quality, also have the benefit of offering a greater counterweight to stock prices in a down market. The current economic expansion is now the longest on record. That doesn’t mean it can’t continue; but, at some point, this expansion like all other expansions before it, will end. And when it does, prices of risky assets are likely to fall sharply as they have in past recessions. Owning bonds that can bounce in such a scenario may moderate portfolio losses.

Quality Dividend-Payers

With a rate cut from the Fed all but guaranteed for July, dividend stocks are back in favor with some investors. Dividend stocks are always fashionable in our view, but Wall Street’s fickle sentiments can result in shifting relative performance for the dividend investor.

Dividend stocks become more attractive to some income investors when bond yields fall, but companies that pay the highest dividends may not be the best dividend stocks to own today. A decade of ultra-low interest rates has encouraged some companies to binge on debt. In an economic downturn, companies with weak balance sheets are more likely to cut their dividends than those with strong balance sheets.

Leuthold Group, an investment research firm, estimated that during the last recession and bear market, companies that cut their dividends underperformed those that didn’t by double digits. Leuthold also reports that over the last three decades, higher-quality dividend-payers have outperformed the S&P 500 by over four percentage points per annum, and did so with less volatility.

We don’t define quality in exactly the same way as Leuthold and are not interested in whether or not our equity portfolio is outperforming broader market indices. Our goal is to craft a portfolio of higher-quality dividend-payers with strong balance sheets that can provide you with a steady stream of income in good times and bad, to meet your personal financial goals. That is the very essence of successful investing.

Have a good month. As always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Warm regards,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. In a recent interview on Bloomberg TV, Rob Arnott from Research Affiliates explained, “If you count up the whole roster of FANMAG companies, that’s the Fang stocks plus Apple, plus Microsoft, their aggregate market value exceeds every market in the world except Japan and the U.S. That’s strange. That surmises that these companies will be world-straddling superpowers in their industries for the foreseeable future and will grow rapidly for the foreseeable future.” That is strange. The idea a few tech firms are worth more than the entire stock markets of the U.K., Germany, or China is nearly unbelievable.

P.P.S. Disney has been having an amazing month, breaking numerous film industry records. The most significant may be that Avengers: Endgame, the epic conclusion of a long arc in Disney’s Marvel Studios’ series of films, became the highest-grossing film of all time, unseating James Cameron’s Avatar. Also in July, a remake of The Lion King grossed $185 million in its opening weekend, breaking the record for July opening weekends, and for films rated PG. Those films followed major financial successes from a remake of Aladdin, Toy Story 4, and Spiderman: Far From Home. The House of Mouse is on a roll.

P.P.P.S. There’s something akin to a bank run happening at some bond ETFs. Despite the easily traded nature of ETFs, when the underlying assets they represent aren’t very liquid, redeeming shares can be a real problem. Bloomberg’s Rachel Evans and Emily Barrett report:

In other words, are exchange-traded funds the ATMs many managers believe them to be? Or will they fail to sell quickly enough and at sufficient prices during a crunch to fulfill customer demands?

“We’ve taken a bunch of semi-liquid securities, put that into an equity wrapper, said now you’re an equity and now you’re liquid,’’ said Deshpande, currently head of fixed income quantitative investments and research at T. Rowe Price Group Inc. “It doesn’t always work that way.’’

Client Portal

Client Portal Secure Upload

Secure Upload Client Letter Sign Up

Client Letter Sign Up