February 2020 Client Letter

A recurring theme surfaced as I was counseling several clients last week: how to maintain a consistent level of comfort with their money during retirement. If you are in or approaching retirement, you are keenly aware that the gig is up in terms of future earning potential. What you have earned and saved must last, potentially for several decades.

Several decades is a long time in retirement. By example, think of the number of news cycles, headlines, and presidential elections you will have to endure. Those without an investment plan and discipline could become susceptible to emotionally charged investment decisions. As Benjamin Graham wrote, “The investor’s chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself.”

Graham is considered one of the greatest investors ever and was well known as a finance professor at Columbia, author of several books including The Intelligent Investor, and a mentor to Sir John Templeton and Warren Buffett.

Less commonly known are the broad areas of knowledge Graham possessed. He was a Greek scholar and, before entering Wall Street, he was offered teaching positions in the subjects of English, mathematics, and philosophy.

Graham was also a student of psychology and appeared to be ahead of his time with regard to behavioral economics. In The Intelligent Investor, Graham cautions investors on the differences between investing and speculating. Right out of the gate in Chapter 1, he writes, “In most periods the investor must recognize the existence of a speculative factor in his common stock holdings. It is his task to keep this component within minor limits, and to be prepared financially and psychologically for adverse results that may be of short or long duration.”

At Richard C. Young & Co., Ltd., our goal is to help you maintain a degree of psychological and emotional comfort during your retirement years. One way we try to achieve this is to develop portfolios that attempt to limit volatility when markets take steep declines.

Gold has historically done a decent job of rising in price when other asset prices drop. We saw an example of this on February 24 when stocks tumbled on fears of an escalation of the spread of COVID-19 (aka coronavirus). As the Dow dropped nearly 900 points one day, the value of GLD climbed 1.8%.

Gold Is Off to the Races

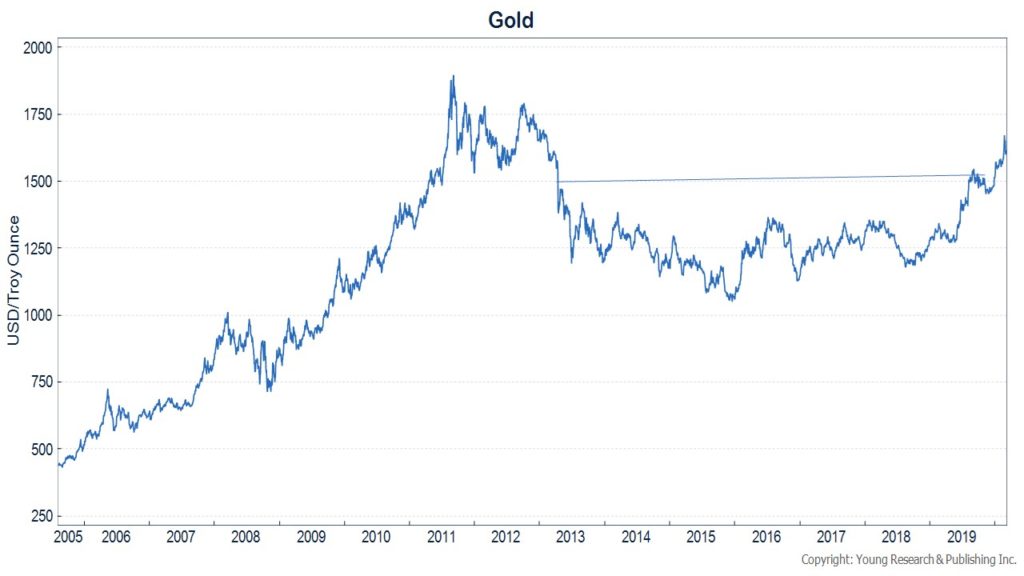

Gold is off to another solid start in 2020 (+8%) after rising more than 18% in 2019. Headlines of rising geopolitical tensions, plunging interest rates, and the coronavirus have been driving the price of gold this year. The bullish price action has some analysts projecting gold will make a new all-time high sometime in 2020. While we aren’t in the business of projecting where the price of gold will be this week, this month, or this year, we do agree that gold’s chart looks encouraging.

Gold broke out of a more than seven-year trading range, as indicated on the chart, and the price has continued to sail through resistance levels.

Helping to fuel the gold rally is continued buying by central banks. Central banks purchased over 650 metric tons of gold in 2018 and 2019. For all the ridicule gold gets from mainstream economists, it is interesting that the institutions charged with maintaining the value of the world’s paper currencies are buyers of gold.

A Major Indicator Sending a Concerning Signal

Any time the price of gold is rising, investors should perk up and be on the lookout for seen and unforeseen risks. That is doubly true when government bond yields are plunging. For the first six weeks of 2020, gold prices were rising,Treasury yields were falling, and the dollar was strengthening.

If you gave me just those three facts, I would have told you that the stock market was probably falling; but, in fact, the opposite was true up until a few days ago. And underneath the performance of the headline indices were speculative rallies reminiscent of the dotcom era. As one example, shares of Virgin Galactic, a firm that hopes to commercialize space travel, had a YTD gain of 223% at its high. The company’s market value reached over $8 billion. Revenues for all of 2019 were $3.7 million.

Quality Being Eschewed

There are, of course, always areas of speculation in the stock market, but the speculative feeling today seems to be pervasive across most sectors and most asset classes. Likely contributing to the fearlessness of investors in 2020 is the rear-view mirror. The 2010s were kind to U.S. stock market investors. There wasn’t a single bear-market (down 20% from peak to trough) in the U.S., and stocks compounded at double-digit rates.

The Big Driver of Stock Returns in the 2010s

The problem with the strong gains in the 2010s was that the biggest driver of those returns may have been the distortive monetary policy pursued by the world’s biggest central banks. When the price of money is held at zero (negative in some countries) for nearly a decade into an economic expansion and the balance sheets of the big three central banks balloon almost fourfold (from 2008), distortion is almost inevitable.

Distortion in Markets is Pervasive

The distortion has manifested itself across all asset markets and in corporate behavior, where cheap debt has been used to finance stock buybacks.

In a recent interview with Barron’s, economist David Rosenberg explained the unique drivers of stock prices during this bull market. (Emphasis is mine.)

Well, what has made this cycle unique is that the correlation between gross-domestic-product growth and the direction of the S&P 500 index has only been 7%. Historically, it has been 30% to 70%. The stock market is telling you nothing about the economy anymore. Economic fundamentals have never mattered as little for the stock market as has been the case during this 11-year bull market. The stock market is behaving more like a commodity than anything else, in that it’s trading on simple supply and demand.

Barron’s asked: Why has that relationship broken down?

“It’s perfect symmetry. We have had $4 trillion of quantitative easing matched perfectly by $4 trillion of corporate share buybacks, to the point where the share count of the S&P 500 is down to its lowest point in two decades. You would normally believe that a powerful bull market in equities would have been reliant on a strong economic backdrop. But that’s far from the case. We have never before seen such a stock-market performance in the face of what has been in the last 11 years the weakest economic expansion of all time. We haven’t even had one year of 3% or better real GDP growth in the U.S. since 2005.

Investors who have captured the full gain in U.S. stocks over the last 10 years may have 1) an extremely high-risk tolerance, 2) a poorly diversified portfolio, or 3) a serious affinity for speculation.

Why speculation?

Based on our internal estimates, about 40% of the return on stocks in the 2010s was driven by investors’ willingness to pay an ever-increasing price for the same stream of earnings. And that 40% doesn’t take into account that earnings per share were boosted by debt-financed buybacks and lower interest expense from the Fed’s ultra-low interest rate policy. Both factors show up in higher earnings per share growth (normally a fundamental driver of stock prices) but have little to do with company fundamentals.

Realized Returns Out of Step with Fundamentals

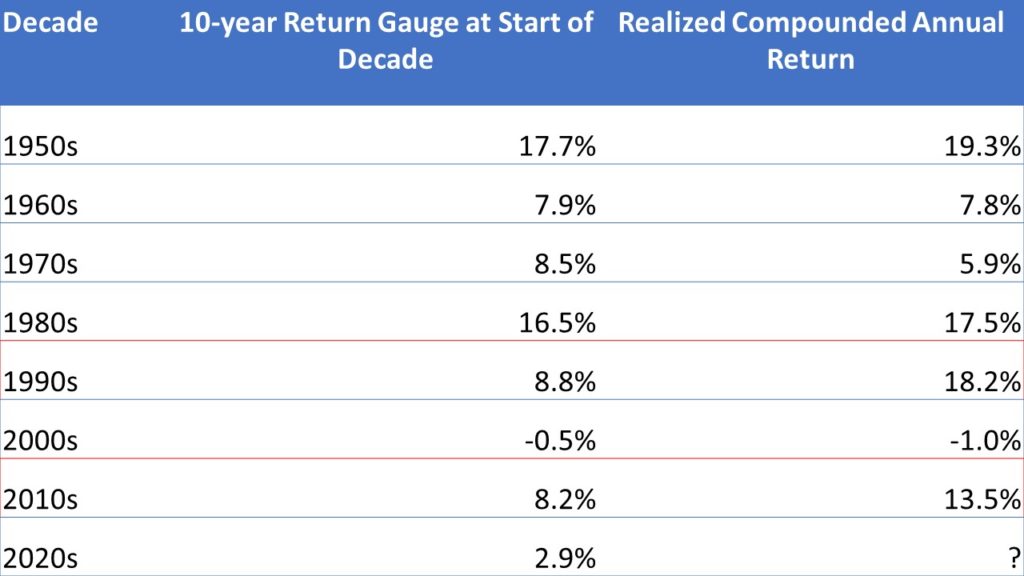

The table below compares the compounded annual return of the S&P 500 each decade with an internal measure we use to gauge long-term total returns. Our gauge does a decent job of getting within a percentage point or two of the realized return for each decade, with two notable exceptions: the 1990s and the 2010s.

In both periods, the returns realized for the decade were significantly higher than our gauge signaled at the start of the decade. In the 1990s, the dotcom bubble drove the market far above fundamental value. In the 2010s, it was a prolonged period of ultra-loose money that drove returns much higher than would be expected based on company fundamentals.

In the decade after the dotcom bust, the giveback was wicked. The S&P 500 lost money over a 10-year period, with two nasty bear markets that cut the index in half on both occasions.

What Will the 2020s Bring for Stocks?

After a decade of distortion in the 2010s that drove returns far above levels indicated by underlying fundamentals, will the 2020s be a repeat of the 2000s, with a similarly dismal outcome for investors?

While it is possible this time is different, if you are retired or on the verge of retirement, the prudent thing to do is to prepare for lower returns and the prospect of another major downturn within the next decade.

How Do You Prepare for the Prospect of Another Stock Market Debacle?

No retired or soon-to-be-retired investor wants to get whacked with the 50% haircut right out of the gate that would come with an all-stock portfolio. Remember, you need a 100% gain to recover from a 50% loss.

To prepare for a decade of potentially below-average stock market returns, we favor balance and dividends. Bonds, even at today’s low yields, provide ballast in a bear market. In the decade of the 2000s, when stocks lost about 1% per year, the Vanguard Balanced Index earned an annual average return of 2.64%—not great, but it was up enough to maintain purchasing power.

A better approach in the 2000s would have been to favor dividend-paying stocks on the equity side of the portfolio. Long dry spells occur for stock prices. Our favored solution to dry spells is to craft a portfolio of stocks that pay relatively high dividends today and offer the potential for dividend increases tomorrow.

Stocks such as IBM, with a 4.6% dividend yield, are the type of firms we favor for the potentially lower return environment ahead. IBM has paid a dividend every year since 1916. How many tech firms have been around since 1916? IBM has also increased its dividend for 23 consecutive years. Over the last five years, the dividend has risen at an 8% compounded annual rate. IBM may not be as sexy a company as Virgin Galactic, trading at 1,650X sales, but buying IBM at 10.5X earnings (not sales) provides a slightly larger margin of safety.

The Bottom Line

The bottom line is that a portfolio of blue-chip dividend-payers, gold, and high-quality bonds can be a way for investors to have confidence in their portfolio, even during periods of uncertainty or volatility. Having confidence and a solid understanding of what you own and what your investment strategy is may help you avoid making financial decisions that disrupt your long-term investment success.

Have a good month. As always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Warm regards,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. Lowe’s is the second-largest home improvement retailer in the U.S. Lowe’s offers a complete line of products and services for decorating, maintenance, repair, and remodeling. The company’s reported financial results for the fourth quarter came in below analysts’ expectations, and the shares were predictably sold down. The fundamentals of the business remain solid, in our view. Lowe’s shares yield 1.94% today, and over the last five years the company has increased its dividend at a 19.6% compounded annual rate. Over the next five years, we would not be surprised if the dividend doubled.

P.P.S. This month you may have read that Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, announced the company would be turning its back on investments in oil and gas for environmental concerns. While Fink may mean well, the industry is still a necessary part of the world’s energy portfolio. BlackRock isn’t the only company making the decision to jettison investments in oil and gas. The downward pressure from news of those defections and recent events surrounding the coronavirus outbreak, has beaten up oil and gas stocks which now make up less than five percent of the market cap of the S&P 500. That’s the lowest level since 1990. Despite being in a rough patch, however, energy demand is not going away.

Energy companies, especially big integrated ones, have much to offer prudent investors today. For starters, their yields are historically high, and many of the integrated energy companies have records of regularly increasing their dividends. Despite the ongoing push toward more solar and wind in the world’s energy portfolio, they aren’t replacing oil and gas any time soon.

Client Portal

Client Portal Secure Upload

Secure Upload Client Letter Sign Up

Client Letter Sign Up