December 2010 Client Letter

With momentum appearing to be behind the stock market, now may be a good time to review one of the most important considerations of investing: risk. Risk tolerance varies among individuals and even varies for the same individual during different market environments and time periods. Because an investor’s tolerance for volatility is subjective, risk tolerance can be difficult to measure precisely.

It’s helpful to read through a stock or fund prospectus to refamiliarize oneself with the broad variety of risks associated with investing. Business cycle risk, liquidity risk, credit or default risk, prepayment risk, currency risk, political risk, and systemic risk are among the usual suspects with potential to cause chaos. Investing in SPDR Gold Trust (GLD) carries several risks including official-sector risk. The official sector consists of central banks, other governmental agencies, and multilateral institutions that buy, sell, and hold gold as a part of their reserve assets. In the event future economic, political, or social conditions or pressures require members of the official sector to liquidate their gold assets all at once or in an uncoordinated manner, gold prices could decline significantly.

During periods of stock-market appreciation, it can be easier to dismiss the potential for loss. As the stock market goes up and our paper gains rise, we can become less sensitive to the fact that markets are always cyclical and unforeseen circumstances remain a constant threat.

Even the smartest folk around can get head-faked. Remember Long-Term Capital Management? Long-Term Capital was a hedge fund in the 1990s whose partners included Nobel Prize winners and MIT PhDs. The company used complex mathematical formulas to assess fixed-income arbitrage deals. The 1998 Russian financial crisis caused havoc for Long-Term’s trading strategies and nearly ruined the financial system. I think it was the Long-Term debacle that inspired Warren Buffett to say “Beware of geeks bearing formulas.”

Many conservative retired or soon-to-be retired investors prefer a mix of both bonds and stocks to help reduce volatility. While investing in a portfolio of all equities may provide the best long-term returns, there is a greater chance for steeper loss than with a broadly diversified portfolio. For those who have spent a lifetime accumulating their wealth, steep losses are an unacceptable outcome.

I periodically highlight the long-term performance of Vanguard’s Wellesley Income Fund. Wellesley, with approximately 60% in bonds and 40% in equities, has posted only six down years since 1970. Perhaps most impressively, the fund was down only 9.8% in 2008. While future results may vary, Wellesley offers a long-term example of how broad diversification can reduce risk and provide comfort for conservative investors.

For years we have used Wellesley as a guide for conservative asset allocation. At Richard C. Young & Co., Ltd., we also incorporate some additional strategies we believe will add value to client portfolios. One of those strategies is including gold and foreign currencies. We began taking initial positions in gold in 2005, and several years ago we added a currency component.

Why We Invest in Currencies

Currency investing is unfamiliar territory for many investors, but it shouldn’t be. The global foreign-exchange market is the largest, most liquid market in the world. According to the Bank for International Settlements, daily turnover amounts to nearly $4 trillion. To put that into perspective, the daily turnover of U.S. stocks is only $40 billion, or 1% of turnover in global currency markets.

The Opportunities in Currencies

Those not investing in the world’s largest market may be forgoing considerable profit opportunities. Currency markets are unique in the sense that not all market participants are motivated by generating profits from their currency trades. Compare this dynamic to the stock market. In the stock market, when you sell a position, the buyer thinks he is acquiring a stock that will move higher while you take the opposing view. Both buyer and seller are most often motivated to trade based on a desire to earn or capture profits. In currency markets, you have central banks, multinational corporations, and individuals, among other participants, who have no opinion on the currencies they are exchanging. Central banks transact in currency markets to manage their exchange rates. A company like Coca-Cola that builds a new plant in Indonesia, by example, isn’t looking to make currency profits on the dollar-rupiah exchange. Coke is more interested in the profits it will earn on the new plant it is building. And a family taking a trip to Europe isn’t exchanging dollars for euros to make a profit. They need euros to pay for goods and services on their vacation. The presence of these non-profit-motivated participants creates opportunities for profit-seekers.

Monetary & Economic Trends in Currency Investing

In our view, currency profit opportunities are best exploited by following a wide variety of global economic and monetary trends. An exclusive focus on the U.S. economy won’t get you far in currency investing. When you buy foreign currency, it is important to understand you are simultaneously selling dollars. In stock-market terms, this is similar to a long-short trade. An investor may buy shares in Home Depot and sell short shares of Lowes. It is not the fundamental performance of Home Depot that determines the return on this position, but the fundamental performance of Home Depot relative to Lowes. Similarly, when you buy the euro, it is the relative fundamentals of the euro and the U.S. dollar that drive the exchange-rate value of the euro. So you can be bearish on the U.S. dollar, but if you are more bearish on the euro, you would buy the dollar-euro currency pair.

Numerous factors can cause an investor to be bullish or bearish on a currency. Valuation, interest-rate differentials, inflation expectations, trade balances, economic growth, price action, and politics and geopolitics can all influence exchange rates over the short and long term. Consequently, currency investors pursue various strategies. Some investors focus on fundamental analysis such as interest rate differentials and valuation, while others rely exclusively on quantitative analysis or technical analysis. Interestingly, both approaches have proven their worth in currency investing.

Purchasing Power Parity and Currency Investing

At Richard C. Young & Co., Ltd., we focus on the fundamentals, with a particular eye on valuation. Like a stock or a bond, an exchange rate has an intrinsic value. Economists refer to this as purchasing power parity (PPP). PPP is based on the law of one price, which states identical goods should sell for the same price in two separate markets.

The most famous example of PPP is The Economist’s Big Mac Index. No matter where in the world you buy a Big Mac, you get the same three sesame-seed buns and two all-beef patties smothered in American cheese and piled high with lettuce, onions, pickles, and McDonald’s special sauce. According to PPP, since you are buying an identical good, the dollar cost should be the same everywhere. To measure the PPP value of currencies, The Economist collects the prices for a Big Mac around the world and translates them into dollars. Countries where a Big Mac is more expensive than in the U.S. have an overvalued currency, and countries where a Big Mac is cheaper than in the U.S. have an undervalued currency. Though the Big Mac Index may sound like a simplistic approach to currency valuation, it is often surprisingly accurate. According to the latest Big Mac Index, the Chinese yuan is undervalued by about 40%, and the euro is overvalued by about 30%. More sophisticated PPP methods come up with valuations that are not far from those generated by the Big Mac Index. Simple is indeed sophisticated.

We, of course, do not base our currency investment decisions on the Big Mac Index, but we do use PPP to value currencies. Over the long run, currencies tend to revert to their PPP values. However, the long run can last for an extended number of years. In the interim, currencies can deviate widely from their PPP values. It is also not uncommon for widely overvalued currencies to become more overvalued before eventually returning to their PPP values. As a result, a currency strategy based exclusively on valuation can be a losing strategy. We supplement our PPP work with an evaluation of relative interest rates, trade positions, political and geopolitical factors, and price action, among other variables. This more inclusive approach results in a diverse portfolio of short- and long-term currency positions.

Our position in the Swiss franc is a longer-term hedge against the U.S. dollar. While we currently believe the franc is richly valued against the dollar on the basis of purchasing power parity, we view it as a hard currency likely to maintain its value even if the deterioration in U.S. currency fundamentals accelerates.

In contrast to our strategy with the Swiss franc, we closed our position in the Canadian dollar earlier this year due to valuation. We continue to favor the underlying fundamentals of the Canadian economy, but at the time of our sale we felt the Canadian dollar’s valuation was stretched. We favor Canada’s long-term prospects and will likely reacquire a position in the Canadian currency when the valuation improves or the country’s interest-rate differential with the U.S. widens.

Interest-rate differentials are the motivating factor behind the position we hold for some clients in Norwegian government bonds. We initiated a position in Norwegian government bonds near the height of the Greek debt panic earlier this year because we felt the currency was oversold, the bonds offered an attractive yield advantage to U.S. treasuries, and the Norwegian government has a net-asset position compared to the massive debt positions of almost every other developed country. We purchased an 11-month bond with a yield of more than 2%. Comparable U.S. Treasuries were yielding only 0.28% at the time.

When Trading Makes Sense

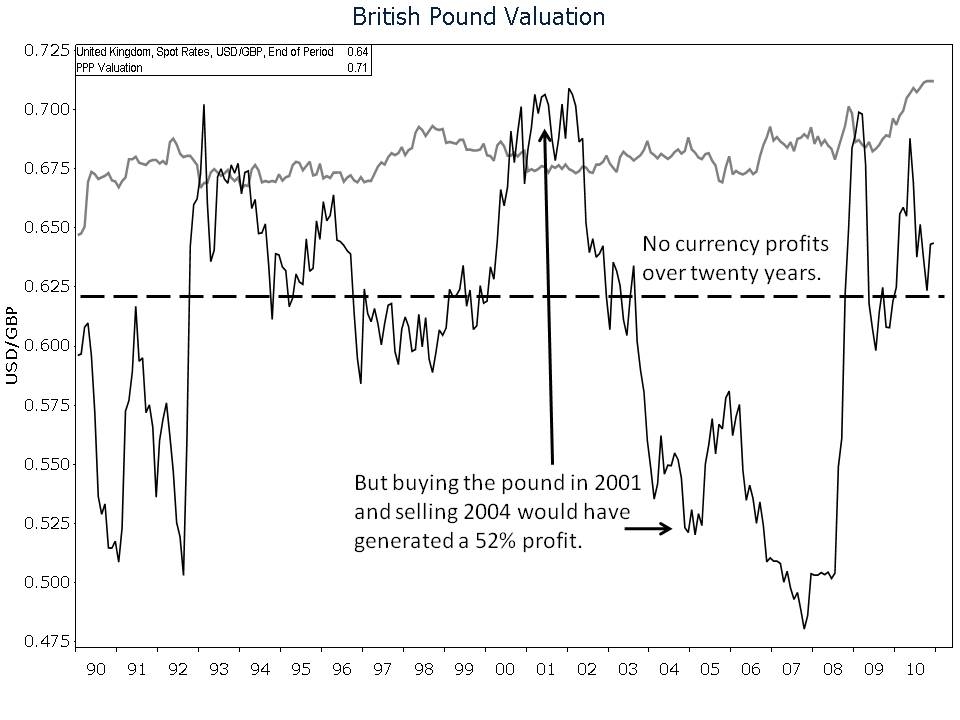

One notable difference between our stock-investing strategy and our currency-investing strategy is that, with the exception of gold, we believe it is advantageous to trade currencies. In the long run, currencies should revert to their PPP rates. Since the PPP rates of most major currency pairs vis-à-vis the dollar exhibit no meaningful long-term trend, one should not expect a sustained long-term gain in a given currency position. My relative PPP chart on the British pound highlights this concept. Over the last 20 years, the PPP value of the pound has changed little. Not surprisingly, there has been no sustained long-term gain or loss in the dollar-pound exchange rate. If you initiated a position in the pound in 1990 and closed the position today, your currency profits would sum to zero. However, if you traded the pound, you could have made significant profits. An investor who purchased the pound at year-end 2001 and sold it at year-end 2004 would have made 52% in only three years.

Expanding our currency diversification as a result of the 2008 financial crisis was just one of the many adjustments made to portfolios during the last two years. Additional adjustments include the sale of all preferred securities and municipal bonds, as well as a greatly reduced position in U.S. Treasury securities. Many of our lower-yielding stocks have been replaced by higher-yielding international companies. Recent foreign equity purchases include Brookfield Renewable Power, Companhia Energética, Innergex Renewable Power, Statoil and Tele Norte Leste Participacoes. We also have less invested in traditionally managed mutual funds. Instead we find value investing in select exchange-traded funds (ETFs). ETFs offer us many diversification options with expenses much less than most traditional mutual funds.

Have a happy New Year and, as always, please give us a call at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Sincerely,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. The investor who has a long-term horizon, or expects to live for many years, faces a risk perhaps worse than portfolio volatility. The erosion of purchasing power by the long-term effects of inflation is a major risk. Historically, the risk of portfolio loss from market declines diminishes over time. The good years should outnumber the bad years, resulting in a long-term positive return. The negative effects of inflation, on the other hand, are amplified with each passing year. We look to offset the effects of inflation by investing in companies that annually increase their dividend, investing in industries with pricing power, and investing in a variety of natural resources, including energy and agriculture.

P.P.S. In an interview with 60 Minutes earlier this month, Ben Bernanke said he feels the fear of inflation is overstated. The Federal Reserve favors the “core CPI” as its measure of inflation. Core CPI strips out food and energy prices. So if you are not concerned with eating or driving, then the effects of inflation should be minimal to you. (Avoiding medical attention, travel, and college tuition are other ways to minimize the effects of inflation). Today we believe inflationary pressures do exist, and investors should be preparing.

P.P.P.S. While the U.S.’s share of the world’s gross domestic product has been declining for decades, profits to U.S. companies from abroad are on the rise. In 2009, the U.S. exported about $1 trillion worth of goods, and it is expected to exceed that in 2010. As the rest of the world expands, demand will increase for airplane engines, cars, computers, and other heavy industrial equipment. Investing, as we do, in big U.S. companies that generate a significant amount of their revenues internationally is a simple way to participate in the growing global economy.

Client Portal

Client Portal Secure Upload

Secure Upload Client Letter Sign Up

Client Letter Sign Up