What’s Going On With Interest Rates?

June 2018 Client Letter

In my January letter, I commented on how it would not be a surprise to see the Federal Reserve raise the Federal Funds rate four times in 2018. When the year started, the Fed indicated it would look to target a total of three hikes this year. In mid-June, as expected, the Fed raised rates for a second time in 2018, bringing the Fed Funds target rate up to 2%. The two additional rate hikes should come in September and December.

How many more times will the Fed raise interest rates before stopping? Many variables go into the Fed’s interest rate decisions; but, historically, short-term interest rates have been as much as 1.5 percentage points higher than the rate of inflation. With today’s Fed Funds rate at 2% and consumer prices rising annually at about 2.2% (as measured by core CPI), the Fed still has significant room to raise rates without overdoing it, even assuming moderate economic growth.

During an economic boom like the one we are witnessing today, the Fed could raise rates higher than 1.5 percentage points above inflation. When the economy gains strength, the Fed gets concerned about overheating and inflation. By raising rates, the Fed increases the cost of money, which slowly but surely feeds its way through the economy and dampens the pace of growth. By example, when short-term rates increase, automobile loan rates rise and consumers buy fewer or less expensive cars. When business loan rates increase, fewer investment projects are undertaken, and when mortgage rates rise, activity and prices in the real estate market tend to slow.

Today’s economy is the strongest we have experienced in years. One of our favorite economic releases is the NFIB small business survey. Small businesses are the life-blood of the American economy. Most new jobs are created by small businesses and almost all big businesses were once small businesses.

The most recent edition of the NFIB small business survey came with welcome news for employees across the country. The highest net number of firms in over three decades are raising pay. A net 35% of small businesses polled report raising compensation over the last three months. This job market is cooking.

You can see it in the Labor department’s jobs numbers as well. The unemployment rate matched a more-than-four-decade low in May. And for the first time on record, there are more job openings than unemployed Americans to fill them.

Job vacancies rose to a fresh record of 6.7 million in April, according to the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS), released by the Labor Department. More importantly, upward revisions to the prior month made it the first time in government data going back to 2000 that job openings exceeded the number of unemployed. That gap of 48,000 in March grew to 352,000 in April and is poised to keep widening, as the number of unemployed has already dropped further in May.

Business investment and new building permits (both leading indicators) continue to gain strength even while interest rates rise. Growth in retail sales has accelerated in recent months, and second-quarter GDP growth may come in at a blistering 4.7%—a rather impressive feat more than nine years into an economic expansion.

Given the strength of the economy and the still-low level of short-term interest rates, we would like to see the Federal Reserve raise rates at least another 1.50%. And the sooner the better.

Bonds are a necessary component of a balanced portfolio, but most investors would agree they aren’t as sexy as stocks. When is the last time you got a bond tip at a cocktail party or heard about the exciting profits your golfing buddies are making in bonds? Bonds can appear dull and complex.

So when you read or hear about interest rates impacting bond prices, it is useful to recognize what interest rate is being discussed and how different interest-rate changes impact the prices of the bonds you hold in your own portfolio.

Short-term and long-term rates are not the same. When I write about the Federal Reserve raising the Federal Funds rate, I am referring to short-term interest rates. The Federal Funds rate is an overnight rate earned and paid by and to banks. The Fed directly controls short-term interest rates, but only indirectly can it influence long-term interest rates.

When the Fed increases short-term interest rates, there is no guarantee long-term interest rates will rise as much as short rates, or even at all. The Fed’s first interest-rate increase during the current cycle was in December of 2015. At the time, the 10-year Treasury rate was about 2.25%. Since early December of 2015, the Fed has increased short-term interest rates by 1.75 percentage points. During this period, long-term interest rates have increased only 0.65 percentage points.

Short-term interest rates are important for asset markets and the economy, but long-term interest rates are where the rubber meets the road. Asset prices and economic growth tend to be more sensitive to long-term interest rates.

We keep a close eye on the 10-year Treasury rate. It broke above 3% earlier this year but has been stuck around 2.9% since. The still-low level of long-term interest rates is at odds with strong economic growth and rising short-term interest rates. Our back of the envelope model for long-term interest rates indicates the 10-year rate should be north of 4% today.

What is holding down long-term interest rates? There are many theories as to why long-term rates remain low in the face of strong economic growth, but we believe global central bank bond-buying has played a leading role. The Fed has been winding down the size of its balance sheet for almost a year, but the pace has been glacial, and European Central Bank and Bank of Japan bond-buying have thus far offset the impact of the wind-down. However, as the year progresses, the ECB will begin winding down its bond-buying program, and the Fed’s balance sheet should begin to shrink at a faster pace. We look for the combination of both factors to push longer-term interest rates higher.

Will the Bond Bubble Crush You?

The financial press, and even some pundits who should know better, like to make blanket statements about the impact of rising rates on bonds. “There is a bond bubble that will crush all investors who own bonds” are common words of wisdom from this crowd. Some bond investors will indeed get crushed. By example, if you own 30-year zero coupon U.S. Treasury bonds, a one percentage point increase in the long bond rate will result in about a 30% drop in the price of that bond. That is one ugly return. But compare that to getting crushed in short-term bonds. Since September of last year, the yield on the Bloomberg Barclay’s 3-5 Year Corporate Bond index rose by 1.3 percentage points, but the index is down just 1.8%. Oh, the horror! That is one of the weaker periods for the index this century; but if that is getting crushed, there is no reason to panic. And if rates increased another 1.3 percentage points over the next year, we would expect 3-to-5-year corporates to end the year flat on a total return basis. With rates now higher, there is more interest income to cushion the blow of a drop in bond prices.

Our strategy in corporates is to roll maturing bonds into higher-yielding and longer-maturity bonds as interest rates rise. That isn’t something that is possible with bond mutual funds.

Saying Goodbye to Vanguard GNMA

With interest rates now at more reasonable levels, we have decided to close our position in the Vanguard GNMA fund. Vanguard GNMA has been fine, but we decided to move the position into Treasuries with maturities of two, four, and five years. With rates on Treasuries and GNMAs now more comparable, we like the increased flexibility Treasuries afford, as well as the better counterbalancing properties of Treasuries.

Treasuries tend to rise more than GNMA bonds when stocks fall. Since March of 1976, the average annualized return of the Bloomberg Barclay’s Intermediate-term Treasury index in down months for the S&P 500 is 5.74% compared to 2.9% for the Bloomberg Barclay’s GNMA index—a difference of 2.84 percentage points. In months when the S&P 500 was down 3% or more, intermediate-term Treasuries outperformed by an annualized 5 percentage points.

Some of the other advantages of Treasuries over GNMAs are that Treasuries are free of state and local tax, whereas GNMA bonds are not. There are no mutual fund expense ratios to worry about with Treasury notes, and a Treasury note portfolio provides more flexibility to better manage opportunities and risks in the bond market throughout the business cycle.

Portfolio Diversification

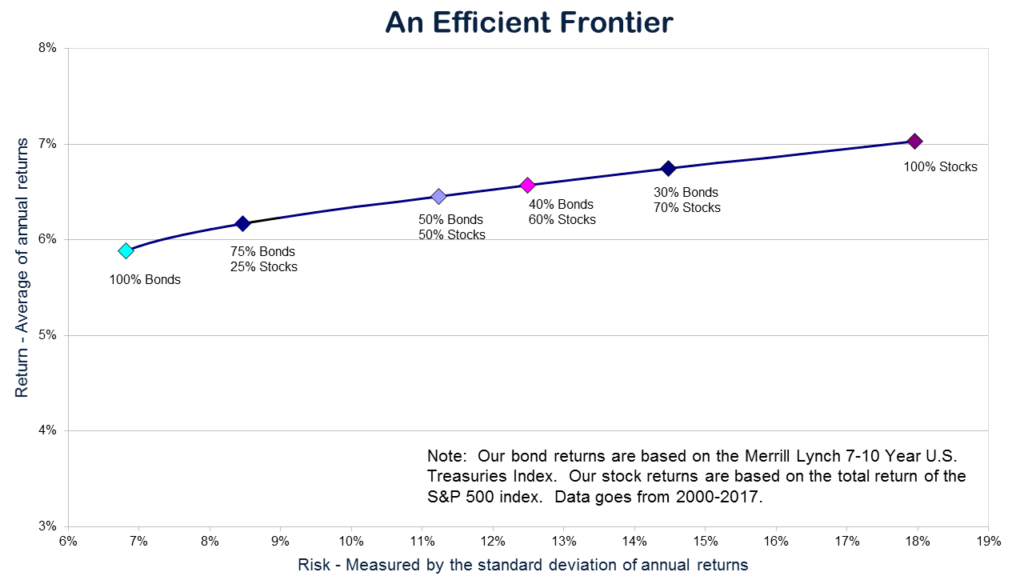

Counterbalancing is at the core of portfolio diversification. Owning assets that don’t move in lockstep tends to lower risk and/or provide a greater return for the same level of risk. Our Efficient Frontier chart below shows the trade-off between risk and return for different balanced portfolios. The returns are for this century and assume annual rebalancing. Moving from left to right, an all-bond portfolio provided the least amount of risk, but also the lowest return. The all-stock portfolio provided the highest return, but it also had the highest amount of risk. Compared to a portfolio with 30% in fixed income and 70% in stocks, the all-stock portfolio earned an additional 0.29% per year, but with 30% more volatility. Retired investors and those approaching retirement may be best served by portfolios inside the two extremes.

It is true that if you shorten the time period to include only the last 10 years, an all-stock portfolio may have delivered a much better return than a balanced portfolio, but don’t forget that markets go through cycles. And the stock market cycles this century have been volatile. From peak to trough, the S&P 500 has fallen by more than 50% twice.

Cycles are also part of the global equity market landscape. Earlier this month The WSJ ran a headline asking if value investors face an existential crisis.

Previously, The New York Times featured a piece on the difficulties of value investing:

Think value investors have it tough these days? Just ask William J. Nasgovitz, portfolio manager of the Heartland Value fund, whose own mother recently tried to pull her money out of the fund.

“My mom wanted to buy Walgreen at 50 times earnings and sell out of the value fund after making six times her money,” Mr. Nasgovitz said. “It’s a great company, but it isn’t worth 50 times earnings.”

He eventually persuaded his mother to stay put. Recently, however, his son Will admitted to buying an index fund. “Another little dagger,” Mr. Nasgovitz said.

And there are many more. “Clients, consultants, and advisers are all tired of talking value,” he said. “They want action.”

“Action” in this case really means one thing: big growth companies and the funds that invest in them.…

But that has lately brought grief for their shareholders, as stocks relatively cheap by traditional measures continue to be clobbered by the big growth companies that have paced the enormous run-up in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index….

Some managers think that with the advent of a new, technology-driven economy—where economic cycles are far longer than they have been in the past—it could be many years before value stocks return to favor for an appreciable period…

Growth stocks were driven up further, they say, by what is sometimes called ”closet indexing”—the purchase of the largest-capitalization stocks in, say, the S.& P. by active fund managers. Some managers moved into these big growth stocks simply because they grew tired of missing out on the market’s momentum…

“As always, when a strong trend has been in place for a few years, there is no lack of people who rationalize why what has been true will continue to be true—in other words, that value, and particularly small value, will never come back,” Mr. Eveillard said [our emphasis added]. “If I thought so, I would retire.”

You may recognize that The NY Times article was written almost two decades ago, in April of 1999.

What motivated The NY Times to write a piece like that near the height of the dotcom bubble? We would assume it was the same thing that motivated The WSJ to write a similar piece early this month—a misguided focus on relative performance. Investors who abandoned value in April of 1999 to chase growth looked smart for a few months; but over the subsequent seven years, value shares crushed growth shares. Over the long run, we believe a value-conscious approach is likely to beat a strategy based on glitz and glamour.

Have a good month. As always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Warm regards,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. Amazon has an amazing business, but the retail operation so many Americans are familiar with isn’t it. There is, of course, no denying Amazon is one of the most dominant forces the retail world has seen in decades. But from a profitability perspective, Amazon’s retail operation is marginal. Over the last 12 months, Amazon retail has made only a single cent in operating income for every $1,000 in sales. That translates to $188 million in operating income on $174 billion in sales.

Contrast that with Amazon Web Services, Amazon’s cloud business. Web services made $4.8 billion in operating income on just $19.2 billion in sales. Only 4% of Amazon’s operating income over the last year came from the retail business. The other 96% came from Amazon Web services.

Investors buying Amazon because it is a dominant e-commerce business might want to reconsider their thesis. Based on its profitability, Amazon is first and foremost a technology business. And a damn pricey one. Amazon shares trade at 265X earnings.

P.P.S. According to the annual Rich States, Poor States report, over the last decade, 3.5 million Americans have moved from the country’s highest-tax states to its lowest-tax states. Arthur Laffer and Stephen Moore, who both worked on the report, told readers of The Wall Street Journal in an April op-ed that the 2017 tax reform will probably accelerate that migration. While 90% of taxpayers won’t be affected by the law’s changes, it will hit the wealthy in high-tax states particularly hard because their state and local income taxes will no longer be deductible at the federal level. Laffer and Moore say this will be a boon for low-income tax states such as Texas and Florida, popular destinations for tax refugees. They write:

Since 2007 Texas and Florida (with no income tax) have gained 1.4 million and 850,000 residents, respectively, from other states. California and New York have jointly lost more than 2.2 million residents. Our analysis of IRS data on tax returns shows that in the past three years alone, Texas and Florida have gained a net $50 billion in income and purchasing power from other states, while California and New York have surrendered a net $23 billion.

Now that the SALT subsidy is gone, how bad will it get for high-tax blue states? Very bad. We estimate, based on the historical relationship between tax rates and migration patterns, that both California and New York will lose on net about 800,000 residents over the next three years—roughly twice the number that left from 2014-16. Our calculations suggest that Connecticut, New Jersey and Minnesota combined will hemorrhage another roughly 500,000 people in the same period.