March 2014 Client Letter

Is rampant speculation bubbling under the surface of today’s stock market? In February, Facebook announced its purchase of WhatsApp, a company with $20 million in sales that was nonexistent before 2009, for $19 billion in cash and stock. WhatsApp is a mobile messaging platform allowing users to send text messages without having to pay for SMS. If you own an iPhone, Apple’s iMessage program basically does the same thing. Seems like a large sum of money for a company whose product appears to be easily replicated.

Then in March, Facebook decided to buy virtual-reality firm Oculus for $2 billion. Oculus is a 20-month-old maker of virtual-reality goggles. Oculus doesn’t yet sell a product that is available to consumers. To date, the firm’s only revenue comes from a prototype sold to developers.

According to The Wall Street Journal, Mark Zuckerberg first met with the Oculus CEO in November. Zuckerberg said that putting on the virtual-reality glasses was “different from anything I’ve experienced in my life.” Maybe Zuckerberg is a visionary, but a $2-billion valuation for what is basically a start-up in a business outside of Facebook’s wheelhouse appears more like a gamble than an investment.

The hype and optimism aren’t limited to Facebook, though. Wall Street is taking advantage of the speculative mood. The investment banks are bringing public anything and everything they can unload on investors. At the current rate, the number of IPOs in 2014 is set to surpass last year’s level by at least 40%.

King Digital Entertainment, maker of the popular Candy Crush Saga game, recently came public at a $7-billion valuation. That’s about equal to the market value of Plum Creek Timber, the largest private landowner in the United States and $2.5 billion more than the market cap of Aqua America—the second largest publicly traded water utility in the nation. Sound fair to you? Based on current earnings and sales, one might argue that King Digital isn’t overpriced. But to date, the company is a one-hit wonder. The bankers underwriting the stock know it, institutional investors know it, and many retail investors know it. So then how does a one-hit wonder successfully execute an IPO at a $7-billion valuation?

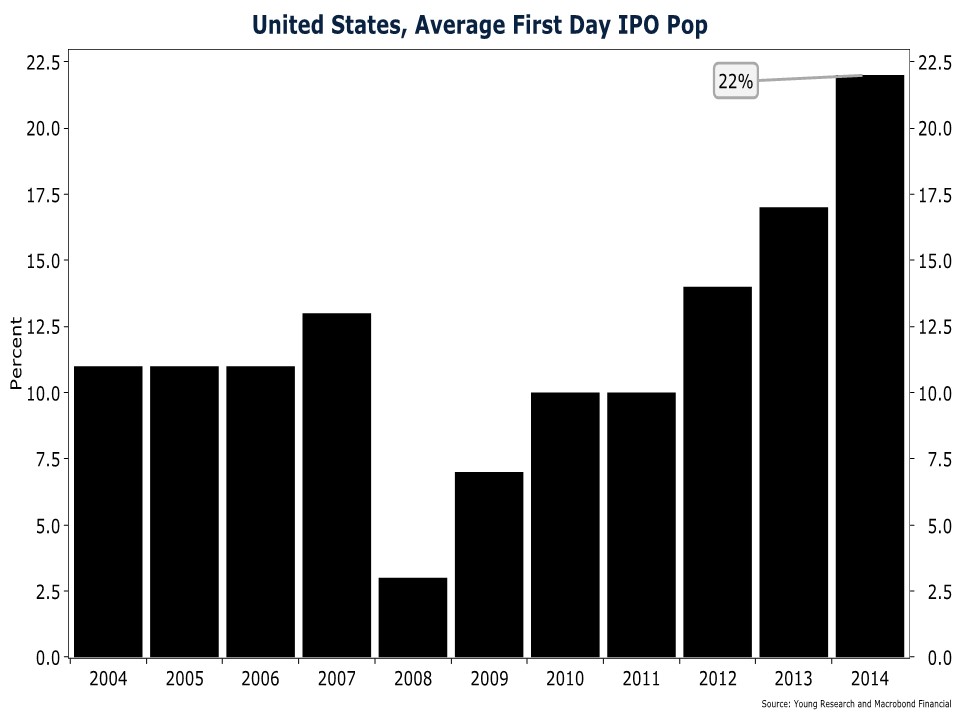

We believe it’s greed. The hope of speculative gains has turned the IPO market red-hot. The chart below sourced from Renaissance Capital shows a 22% average one-day pop in IPOs in 2014—the highest in over a decade. Investors participating in the King Digital IPO were hoping to make a quick buck as they did with many of the other IPOs that came public in 2014.

There is also anecdotal evidence of Wall Street research analysts returning to dubious practices that were a staple of the dot-com bubble. Tesla Motors shares soared in February after Adam Jonas, the Morgan Stanley analyst covering the company, upgraded the stock. Mr. Jonas decided that Tesla wasn’t worth the $153 per share he had estimated only a few weeks prior, but instead priced the stock at $320 per share—a more than 100% revaluation.

We don’t follow Tesla shares closely, but the doubling of a price target grabs attention.

Apparently, Mr. Jonas decided to double the price target of Tesla because he saw profound promise in the company’s yet-to-be-announced plans for a battery factory. This pie-in-the-sky analysis implies that Mr. Jonas simply fell prey to a bubble-induced euphoria that caused a lapse in judgment. No harm, no foul, right?

Not a chance. This is Wall Street we are talking about.

Two days after the upgrade, The Wall Street Journal reported that Tesla was issuing $1.6 billion in convertible bonds to help finance the battery factory. Can you take a wild guess at who underwrote the bonds? It was none other than Mr. Jonas’s employer, Morgan Stanley.

If you thought these potential conflicts of interest were a thing of the past, think again. Wall Street is in the business of distributing securities. And brokerage clients are a convenient dumping ground for newly issued securities.

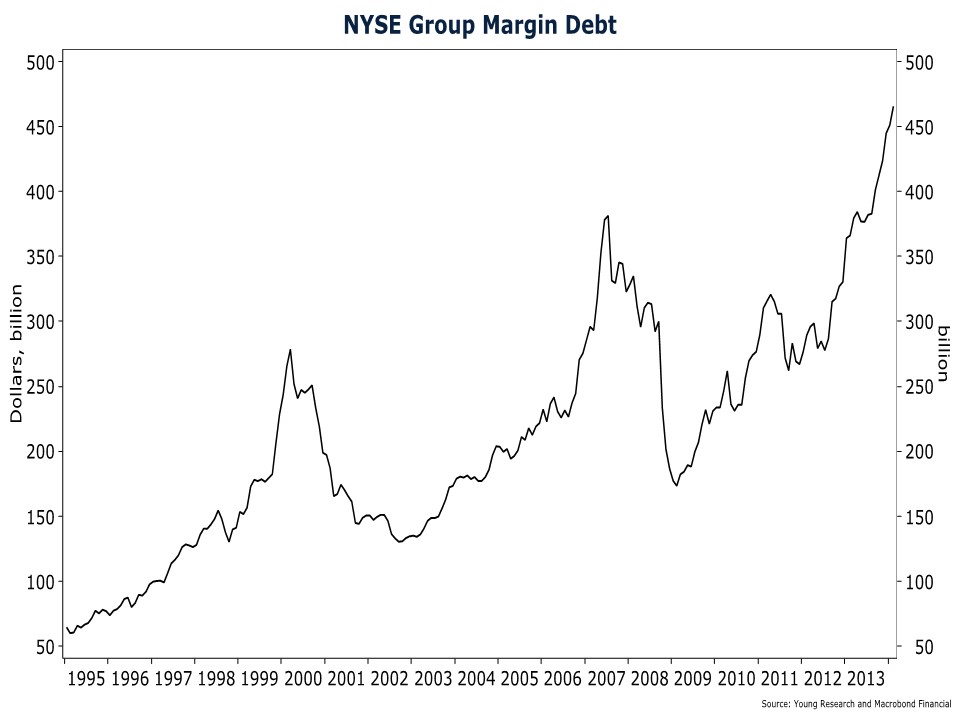

Another sign of the speculative fervor in the market is the level of margin debt. Emboldened by a prolonged period of 0% interest rates and an especially slow wind-down of the Federal Reserve’s bond-buying program, investors are piling on the leverage. Our chart shows margin debt has reached a record high.

Margin may sound like a good idea when prices go up, but on the way down, margin can be devastating. If you buy a stock with 50% margin and the shares drop 20%, you don’t lose 20%— you lose 40%! Even if you take a more conservative approach to margin and buy funds instead of an individual stock, margin could sting. In the 2008 calendar year, the S&P 500 fell by 37%. A 50% margined investment in the S&P 500 in 2008 would have lost you 74%—assuming, of course, you were able to meet your broker’s margin calls.

To craft an investment portfolio to help reduce steep volatility, investors must be willing to forgo potentially substantial upside rewards to balance against a downside wipeout. If you are retired or saving for retirement in the not-too-distant future, you can easily get a knot in your stomach when you look at the basic math of downside portfolio protection.

By example, if you lost 74% on your margined S&P 500 position, you would have to make 280% on the next trip to the plate just to get back to even. Even if you don’t use leverage, the S&P 500 fell by 37% in 2008—a loss that requires a 60% gain to get back to even. And that’s without considering the negative drag of expenses, potential taxes on any gains, and overcoming income pulled from the portfolio to satisfy distribution needs. Things can get real ugly—and fast.

To help reduce substantial losses all too common in the aftermath of a speculative bubble, we advise a strategy that can provide comfort and confidence. Focus on personal goals and objectives and ignore the pundits and promoters trying to seduce you with promises of speculative gains.

Take a realistic view of the gains the market is capable of delivering in the current environment. Stocks have come a long way over the last five years. Investors still forecasting 10% returns for the foreseeable future are likely too optimistic. Why? For starters, dividend yields are a fraction of what they used to be. The historical average dividend of the S&P 500—before the modern bubble era—was 4%. Today, the S&P 500 yields less than 2%. Valuations are also much richer than they were in decades past. The S&P 500 trades at a cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio (CAPE) of 25X today. The historical average 10-year return of the S&P 500 when the starting CAPE is 21X–25X is about 4%.

Bonds are also likely to deliver less than they have historically. The secular decline in interest rates that began in the early 1980s and brought the 10-year Treasury yield from over 15% to under 2% is finished. Yields are now lower, and the tailwind from falling interest rates that added to bond returns is gone.

This doesn’t mean bonds will suffer colossal losses over the medium term. Measured inflation looks to be contained for now, and we are late in the business cycle. Interest rates may not rise as much as they typically would when the Fed begins to tighten policy, simply because the next recession is nearer than it usually is at this stage of the cycle. Investors who limit the duration of their portfolios are unlikely to suffer major losses. A bond portfolio with a duration of 4 would only drop by 4% if interest rates instantly increased by 1%.

As for investment strategy, it’s important to recognize that the uncertainty of today’s environment is amplified by the Fed running a full-tilt monetary stimulus program. Stock prices could continue to rise before the current cycle is complete. And there is no guarantee that today’s market will collapse in the same manner as in the past. It is possible (though not probable) that the market will correct by drifting sideways for an extended period of time, during which company fundamentals will catch up to prices.

Over the long haul, a portfolio balanced across asset classes is generally the best idea for conservative retired and soon-to-be-retired investors. That’s not because balanced portfolios will necessarily post the highest long-term returns—over most long time periods, stocks have posted the highest returns. Rather, balanced portfolios tend to work best because investors find it easier to ride out market volatility with this type of portfolio. By diversifying, investors help themselves to avoid the fear and regret that can emerge when the financial markets take a dive.

Have a good month, and as always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Best regards,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. Where possible, we look to buy securities that are out of favor. In today’s environment, that has become difficult to do. But there are still some good candidates—most businesses related to precious metals are viewed as ghastly and grizzly by institutions and individuals alike. Precious metals shares have taken a savage beating, both on an absolute basis and relative to gold. The Market Vectors Gold Miners index is down over 60% from its highs in 2011 and almost 50% since year-end 2012. You would be hard pressed to find a sector in the market that is more out of favor.

P.P.S. We have been purchasing shares of various gold and silver mining companies. The initial positions are small, but we plan to increase our allocation to precious metals miners over time. With metals miners deeply out of favor, we view the sector as one spot in the market offering value to long-term investors. Some miners are trading near levels they were at when the metal they produce was 30% cheaper than today.

P.P.P.S. We recently updated both Part 2A and Part 2B of our Form ADV as part of our annual filing with the SEC. This document provides information about the qualifications and business practices of Richard C. Young & Co., Ltd. If you would like a free copy of the updated document, please contact us at (401) 849-2137 or email Christopher Stack at cstack@younginvestments.com. There have been no material changes since the document was last updated on March 26, 2013.

Client Portal

Client Portal Secure Upload

Secure Upload Client Letter Sign Up

Client Letter Sign Up