February 2017 Client Letter

It took nearly 18 years for the Dow Jones Industrial Average to go from 10,000 to 20,000. Factoring in time and return, that works out to a compounded annual gain of 4.2%, not including dividends. And that’s the key—not including dividends. In fact, while the Dow doubled from its March 29, 1999, level, when you factor in dividends, the total return becomes 205%. In other words, more than half the return of an investment in the Dow during this period was delivered by dividends.

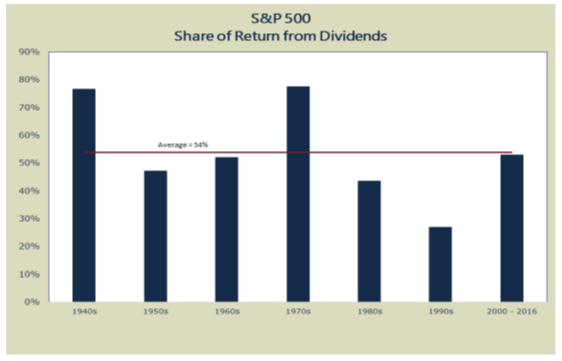

Savvy investors have known for decades that dividends are a vital component of long-term stock-market returns. During day-to-day and month-to-month periods, dividends may seem trivial, but as our chart below shows, over the last seventy-plus years, dividends have accounted for a majority of stock-market returns.

Dividends can play an especially important role when valuations are elevated (as we would argue is the case today) and appreciation potential is limited. In the first 15 years of this century, the ultra-low dividend-paying Nasdaq Composite Index didn’t gain a single point. However, an investment in high-dividend-paying stocks compounded investors’ money at 7% per year. And during the 16 years from 1965 to 1981 when the Dow delivered nothing in the way of capital gains, high-dividend-yielding stocks gained 8.1% annually.

Companies that pay dividends and make regular annual dividend increases provide a rising stream of income that lays the groundwork for rising share prices. At Richard C. Young & Co., Ltd., dividends are the focus of our common-stock investing strategy. We favor companies that pay dividends and have a history of making regular annual dividend increases.

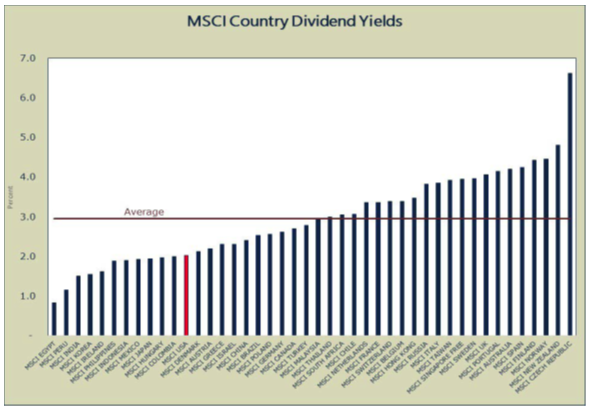

Our search for dividend stocks is not limited to the U.S. We craft global dividend portfolios. You may be familiar with the benefits of international diversification, but did you know that many foreign markets offer yields much higher than those on the U.S. stock market?

Our chart shows that, of the 44 countries in the MSCI All-Country World Index, the U.S. ranks 33rd in terms of dividend yield. Some of the markets we favor today offer yields nearly double those of the U.S. market.

Sweden a Favored Foreign Market

Sweden has long been one of our favored foreign markets. Why do we like Sweden? For starters, the Swedish stock market offers a yield almost double that of the U.S. market.

Sweden is also one of the world’s most innovative economies. The perception many people have of Sweden is that of a bureaucratic nightmare. A socialist state taxing at 100%. A currency in turmoil. This was the reality in Sweden during the ’70s, but no more.

Anders Borg, the fantastic former Swedish Finance Minister who deserves a great deal of the credit for turning the country around, explained Sweden at the time like this: “Well, our experience in the ’70s and ’80s with exchange rates is very bad. It was a part of the vicious circles of excessive wage increases, inflation, low productivity, losing competitiveness, devaluing the currency. Then we started out with too high inflation, too high wage increases, low productivity and we devalued the currency. So it was a vicious circle that just keeps going, and fundamentally you cannot build a prosperous society on devaluing your currency.”

Today, Sweden is one of the freest and most prosperous countries in the world. Since 1996, Sweden’s real annualized quarterly average GDP growth rate has been 2.5%, while the euro area only achieved 1.7% growth during that time. In 2012 Borg told an audience about the country’s turnaround and how it helped Sweden weather the Great Recession. “So basically, Sweden has weathered this crisis in a pretty solid manner. I think part of that has to do with the fact that we have done very substantial structural reforms of our economy.”

The Cato Institute lists Sweden 15th overall on its Human Freedom Index, which measures personal and economic freedom in order to rank countries around the world. In fact, in 2016 Sweden celebrated the 250th anniversary of its ground-breaking Freedom of the Press Act, the world’s first freedom of information legislation.

Sweden has also become the world’s second-most innovative economy. Unlike many of the Eurozone countries, Sweden has remained focused on research and development. Thanks to laws that promote individual innovation and entrepreneurship, Sweden has risen to second place on the 2017 Bloomberg Innovation Index.

We currently gain exposure to Sweden through our investments in Fidelity Nordic, Atlas-Copco, and Swedish Match.

Stick with Dividends through Thick and Thin

Like all investing strategies, dividend investing tends to fall in and out of favor. Last year, dividend stocks led the market, but year-to-date the technology-focused FANG stocks (Facebook, Apple, Netflix, Google) are investors’ darlings and dividend shares are lagging.

We would of course prefer to see our dividend-focused portfolio on top every quarter of every year, but we do not alter our strategy simply because it is not popular at the moment. Remember it is not from day to day or month to month when dividend investing shows its prowess; rather it is over years and decades when dividend strategies shine.

The same holds true for individual dividend-paying companies. Some firms or sectors may fall out of favor, but if we believe a company can maintain its dividend and preferably increase its dividend over time, we have no problem riding out rough patches.

Our investment in pipeline MLP stocks provides a recent example of our commitment to this principle. In late 2015 and early 2016 when oil prices plumbed fresh lows, pipeline shares fell deeply out of favor with investors. The losses were significant and many investors bailed out of pipeline shares. Our view was that many of the pipeline companies had the ability to maintain their dividends, so we held most of our positions and even increased our exposure to the sector during the sell-off.

How have pipeline shares performed since hitting multi-year lows last February? The Alerian MLP Index (AMZ) is up over 70%. It is of course never pleasant riding out a nasty correction in any company or sector of the market, but in our experience more often than not, patience is the best approach with dividend payers.

BB&T and IBM

We recently added BB&T and IBM to client portfolios. Both companies have a strong record of making regular annual dividend increases.

BB&T is one of the largest regional banks in the country, with 2,220 financial centers in 15 states and Washington, D.C. BB&T is active in consumer and commercial banking, securities brokerage, asset management, mortgage lending, and insurance. BB&T has been named one of the world’s strongest banks and one of the top three in the U.S by Bloomberg Markets.

Thanks to a conservative lending culture and the astute management of the now-retired John A. Allison, BB&T was one of the best positioned banks going into the financial crisis.

During Allison’s tenure as CEO, shareholders earned a compounded annual return of 10.7% compared to a 4% for the S&P 500 Financials Index. John Allison is no longer the CEO of BB&T, but the company remains well managed. The bank is well capitalized, generates a significant share of income from fees, and continues to have a more conservative lending strategy than many of its competitors. Most importantly, there is a strong commitment to shareholders and the dividend.

IBM is the only technology company that has reinvented itself through multiple technology eras and economic cycles. The company was founded in the late 1880s to produce punch-card data-processing equipment. Over its long and storied history, IBM has sold a wide range of business equipment, including time-keeping systems, weighing scales, automatic meat slicers, coffee grinders, punch-card equipment, clocks, time-recording equipment, typewriters, computers (IBM had a 70% market share in 1964), mainframes, and software.

In a sector where 60% of companies are estimated to have experienced catastrophic loss (70% decline with minimal recovery), IBM has proven its ability to adapt and thrive.

Today, IBM is transforming itself again, from an old-line hardware, software, and services company to a cognitive solutions and cloud platform company. IBM explains cognitive solutions as technology that “includes, but is broader than, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural language processing.”

The embodiment of cognitive solutions is IBM’s Watson, named after the company’s first CEO, Thomas J. Watson. Watson can reason as well as generate hypotheses, arguments, and recommendations. Watson learns from experts and from its own experience. This offers the opportunity to vastly improve decision-making and turbo-charge productivity across a wide and growing range of industries.

In our view, the opportunity in cognitive technologies is truly profound, and IBM is a leader in this space. IBM is not the only player in artificial intelligence, but it is the only firm to top the list of U.S. patent recipients for 24 consecutive years, and it is the only firm with the world’s largest private-industry math department.

All Eyes on Tax Reform

With the election of the new administration, and single-party control over the nation’s legislative and executive branches of government, the time seems ripe for tax reform. Members of both major parties have agreed for some time that America’s corporate tax rate is holding its companies back, but differing views on the proper fix have conspired to sink even the best attempts at finding bipartisan support for a bill. Remember Simpson-Bowles? The Gang of Six?

With the Trump administration and the GOP-led House and Senate mostly agreed on the outlines of what tax reform should be, it’s likely there’s a bill coming. Newly confirmed Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin says he wants a bill on the president’s desk before Congress goes to recess in August. What will ultimately be in the bill remains in flux.

Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform, has written an outline of what he believes is likely to end up in the final legislation, and what is less certain.

Which Reforms Are in, and Which Are Out?

On Norquist’s list of likely reforms is the abolition of the federal estate tax, the repeal of the alternative minimum tax, individual tax cuts, corporate tax cuts and a shift to a territorial taxation system that will allow American corporations to bring home money from abroad without penalty.

According to Norquist, a few other pieces of the GOP’s plan remain up for debate. The foremost of these is the border adjustment tax. Norquist seems to believe it will make it into the final bill, but it faces a stiff lobbying effort by importers who want it killed. The tax could raise $1 trillion in revenue over ten years, offsetting the declines in revenue from the overall corporate rate reductions being proposed. Another planned reform sitting in limbo is the elimination of interest-payment deductions. Norquist warns to watch for exceptions made for regulated industries like power plants, which benefit from such deductions. The final reform Norquist points to for further study is the “deferral of capital gains taxes for ‘like-kind’ exchanges.” This tax cut would allow businesses to defer capital gains taxes if they, say, generated the gains on a small truck but then used them on an “in-kind” purchase such as buying a bigger truck.

Investors are rightfully enthusiastic about individual and corporate tax reform; but if history is any guide, this enthusiasm should be tempered. What gets passed often looks a lot different from what is discussed over the course of a campaign. The last time the U.S. passed comprehensive tax reform was in 1986, and it took two years to hammer out the law. Granted that law was passed by a slow-moving divided government, but even with single-party control, tax policy is complex and far reaching. No industry will hold back on its lobbying efforts as everything will be affected by tax reform.

Have a good month. As always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Warm regards,

Matthew A. Young

President and Chief Executive Officer

P.S. In describing the global monetary policy by the world’s central banks, my dad recently wrote, “The Fed stopped printing money in 2014 and has begun raising interest rates, but just as Yellen let off the monetary accelerator, her Keynesian counterparts in Japan and the euro area kicked on the nitrous oxide. And in a world of freely flowing capital, the Fed doesn’t have a monopoly on market distortion. The Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank can be equally distortive. The unprecedented intervention in markets has gone on for so long that it now feels normal to many, but I assure you there is nothing normal about the Bank of Japan printing money to buy equities or the European Central Bank doing the same to buy corporate bonds.”

P.P.S. After selling off as interest rates spiked following the election, gold has made something of a comeback in 2017. Gold is up over 9% YTD compared to about a 6% gain in the S&P 500. The rally in gold seems at odds with the prevailing sentiment in the stock market. Stock market investors are bullish. The Dow has been up for 12 consecutive days. Gold and stocks don’t often rise in tandem like they have over the last two months.

Is gold trying to tell us something? Is calamity on the horizon? Are rising gold prices a signal that goods inflation is about to rear its ugly head? Is the growth acceleration that has been baked into stock prices unlikely to materialize? Is gold telling us that the dollar has peaked? Maybe it is China or the prospect of a euro breakup that is pushing gold higher.

Whatever the reason for gold’s recent appreciation, we include gold in portfolios as an insurance policy of sorts for when undesirable events materialize. Or, as Jim Grant, the publisher of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer told a crowd last summer at a conference of the New York Society of Security Analysts, “The case for gold is not as a hedge against monetary disorder, because we have monetary disorder, but rather an investment in monetary disorder.”

P.P.P.S. China has gained massive market share in manufacturing over the last 15 years. Cheap labor and a managed currency helped China become the world’s go-to factory. But as the FT recently reported, China has now lost its edge in labor. Wages in China are now higher than they are in Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico.

What happens to the low-cost producer when it loses its edge on cost? China could either try to regain competitiveness by devaluing the yuan (a bad choice) or attempt to move up the value chain (a better choice). Whichever direction the country takes, the global economic landscape is likely to take on a new shape.

Client Portal

Client Portal Secure Upload

Secure Upload Client Letter Sign Up

Client Letter Sign Up