May 2016 Client Letter

From the time he took over the Windsor Fund in 1964 until his retirement in October 1995, John Neff delivered to his shareholders one of the most impressive returns in mutual fund history. Over Neff’s 31-year tenure at the helm of the Windsor Fund, a $10,000 investment grew to over $564,000. That same $10,000 investment in the S&P 500 would have grown to only $233,000—the average annual return difference between Windsor and the S&P 500 was only about 3% per year; but compounded over three decades, it resulted in an extra $331,000 of wealth.

The Forlorn, the Unloved, and the Out-of-Favor

In an age when large mutual funds struggle to even keep pace with broader market averages, how did Neff, who at one point was managing the nation’s largest mutual fund, manage to achieve such impressive results?

As my dad explained in a recent investment strategy report, Neff had a unique investing style.

John Neff, in his Vanguard Windsor Fund days, was an outstanding proponent of investing in the forlorn, the unloved, and the out-of-favor. John was noted for his patience and willingness to be out of synch for extended periods. During my institutional brokerage days, I loved working with Wellington Management, Windsor Fund’s management company. I knew many managers and analysts at Wellington and fondly remember, when I was the new kid on the block with a lot to learn, the helpful, informative lunches and analyst sessions. These learning sessions still serve me well today. And the contrary-opinion, out-of-phase success of John Neff played a big part in the learning curve I share with you over four decades later.

My dad goes on to explain:

… It is during a Neffian cycle that the dividend-paying stocks I favor tend to have their worst relative performance versus the stock market in general. Over long periods, Windsor Fund’s John Neff found himself wildly out of synch. John invested primarily in low P/E stocks, which is quite different from what I do. John’s low P/E stocks often fell out of favor. Neff simply did not care and stuck to his guns through thick and thin, often taking a beating in the “what’s hot today” financial media. I remember critical articles about John’s out-of-synch performance—each more misguided than the previous. John was not investing to outpace his neighbor. Rather, he was investing client funds entrusted to him with diligence, care and prudence, as if he were investing his own family fortune.

In his latest quarterly letter, Ben Inker, the co-head of Asset Allocation at Jeremy Grantham’s GMO (a firm with serious contrarian bona fides) offered readers some insight and counsel on the toll the Neffian cycle has taken on his own firm’s value-based approach.

Inker explains:

It’s no secret that the last half decade has been a rough one for value-based asset allocation. With central bankers pushing interest rates down to unimagined lows, ongoing disappointment from the emerging markets that have looked cheaper than the rest of the world, and the continuing outperformance from the U.S. stock market and growth stocks generally, it’s enough to cause even committed long-term value investors to question their faith. Over the past several years, we at GMO have questioned a lot of things, including assumptions that we had held without much question for decades, but we have not wavered in our belief that taking the long-term view in investing is the right path and that in the long run no factor is as important to investment returns as valuations.

The drivers of mean reversion [Editor’s note: the heart of GMO’s value strategy] are not hugely powerful at any given time, meaning asset prices and even the underlying fundamentals can move in unexpected ways for disappointingly long periods. It is a little glib to say that without this risk, it would be difficult for asset prices to get meaningfully out of line in the first place, but the reality is that the only way you can get really exciting opportunities for mean reversion is to have misvalued assets become even more misvalued before they revert to fair value. This is the catch-22 of value-driven investing. Your best opportunities will almost always come just at the time your clients are least interested in hearing from you, and might possibly come at the times when you are most likely to be doubting yourself. [Emphasis mine.]

In our view, an appreciation and understanding of what my dad refers to as the “Neffian cycle” is important to long-term investment success.

Diversification and Patience

We of course do not pursue a low P/E strategy like Neff, or a value-based asset allocation strategy like GMO. Diversification and patience form the foundation of our strategy. We craft portfolios that are diversified across asset classes and countries. In equities, we take a value-conscious approach focused on companies with a record of making regular dividend payments and regular dividend increases.

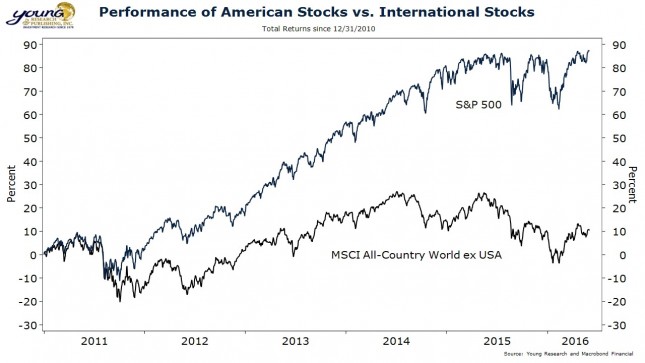

Like at GMO, the last few years have not always been kind to some of our favored asset classes. The relative performance of international shares has been especially challenged during this period. Our chart shows the performance of the MSCI All-Country World Index, excluding the United States in relation to the performance of the S&P 500. Over the last five years, international shares, as measured by the MSCI index, have lagged their U.S. counterparts badly.

Despite what some might consider to be a painfully long period of weak relative performance, we continue to own and add to our international holdings. Why? The way we see it, the investment criteria we use for selecting international stocks is largely the same as it is for selecting U.S. stocks. We favor dividend-paying companies which have records of making regular dividend increases. We further favor firms with strong financial positions and those operating in industries with high barriers to entry. The companies we buy may not be household names to all Americans; but, in our view, their investment merits are just as good as the domestic names we own.

Take Siemens by example. Siemens is the GE of Germany, though it may not be a household name in the U.S. The company is an industrial conglomerate with businesses in power and gas, renewables, power generation, energy management, building technologies, and healthcare, among others. Siemens ADRs pay a 3.6% gross yield and the company has increased its dividend (in euros) at a compounded annual rate of 10% over the last decade. Siemens shares trade at a price-to-estimated-earnings ratio of 12.7X compared to 17.4X for U.S. firms in the same industry group. With Siemens, you get yield, you get value, and you get a global industrial powerhouse.

Bond Sentiment Today Unlike Anything We Have Seen

Another asset class that has experienced a Neffian cycle of its own in recent years is bonds. Bonds have lagged stocks, as they often do during bull markets, but the sentiment we are seeing towards the bond market today is not quite like anything we have seen before.

There is no denying that investing in the bond market has been a tough slog over the last few years. Zero percent policy rates and bond buying by the world’s major central banks has kept bond yields at some of the lowest levels on record. Investors have long had an aversion to the bond market, partly because bonds don’t offer the glamor and hope many crave from their investments. And bonds don’t provide the kind of long-term upside stocks can provide. Add today’s ultra-low yields to the investing public’s natural bias against bonds, and the result is a move by some investors to load up on stocks in an effort to boost income.

Higher yields are indeed available in the stock market, but bonds shouldn’t be bought solely for income. Bonds provide the courage to own stocks. They are a powerful counterbalancer. When stocks fall, bonds often rise. For retired investors drawing income, bonds can be viewed as a stabilizer.

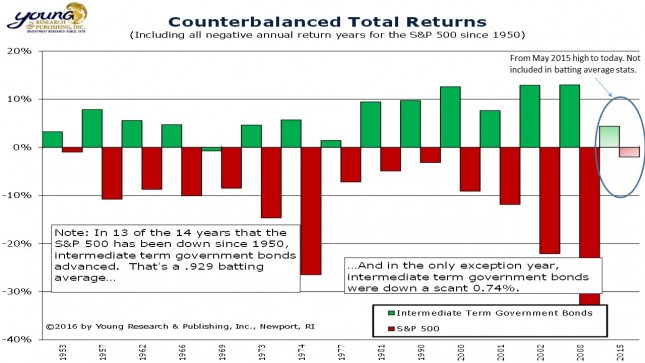

Our chart below shows the performance of bonds in every calendar year the stock market has been down. In 13 of the 14 years that the S&P 500 has been down since 1950, intermediate-term government bonds advanced. That’s a .929 batting average. And in the only exception year, intermediate-term government bonds were down a scant 0.74%.

We haven’t seen a calendar down-year for the stock market since 2008, but the last two bars on our chart show the performance of the S&P 500 from its May 2015 high through today. From its May 2015 high, the S&P 500 is down about 2% and, as you would expect, intermediate-term government bonds advanced—by 4.4%.

Despite today’s painfully low yields and what appears to be a widely shared view among the investing public that income stocks are a replacement for bonds, we believe bonds remain a useful component of a well-diversified portfolio.

Focusing on Quality and Keeping Maturities Short

With yields so low, what is our current strategy in the bond market? We are focusing on quality and keeping maturities short.

Since 1945, the average business cycle expansion has lasted about 58 months. The current expansion is in month 83. By our estimation, that puts us at least in the winter stage of the cycle. In the late stages of an expansion, balance sheet leverage tends to rise and earnings quality begins to fall, leading to deterioration in creditworthiness.

The winter stage of the business cycle is not the time to take excessive credit risk. Late last year we began the process of upgrading the credit quality of our fixed-income portfolios. We sold the Fidelity Floating Rate High Income Fund, which invests in lower-rated firms, and boosted our position in full-faith-and-credit-pledge Treasuries and GNMA securities.

In a normal cycle where the Fed had already normalized interest rates, we would usually be looking to invest in longer-maturity Treasury securities, as these bonds often provide more upside during the contraction phase of the business cycle. But today, with the Fed only a quarter point off of zero and negative rates across much of the developed world, yields on long-maturity Treasuries are at levels that have historically been associated with recessionary conditions. That leaves limited upside should a recession occur and significant downside should the economy escape recession. As a result, we’ve stayed short with our government bond positions.

So far this year, a quality approach has not been rewarded. Despite the long duration of the expansion and deteriorating credit fundamentals, the lowest-quality bonds have performed the best in 2016. A reversal in oil prices, which were putting stress on many issuers in the high-yield bond market last year, has helped the sector. Aggressive policy actions by the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank (ECB) have also likely helped lower-quality corporates in 2016. The Bank of Japan lowered rates into negative territory, as did the ECB. And the ECB went so far as to announce a plan to buy corporate bonds, including those issued by euro-area subsidiaries of U.S. firms.

In our view, because of the resulting policy actions of the world’s major central banks, we now have a situation that has become familiar over recent years—monetary policy is distorting asset prices. We believe with credit fundamentals deteriorating and what we consider to be an artificial pricing element in the corporate bond market, an emphasis on quality remains the prudent investment strategy.

Have a good month. As always, please call us at (888) 456-5444 if your financial situation has changed or if you have questions about your investment portfolio.

Warm regards,

Matthew A. Young,

President and Chief Executive Officer

Client Portal

Client Portal Secure Upload

Secure Upload Client Letter Sign Up

Client Letter Sign Up